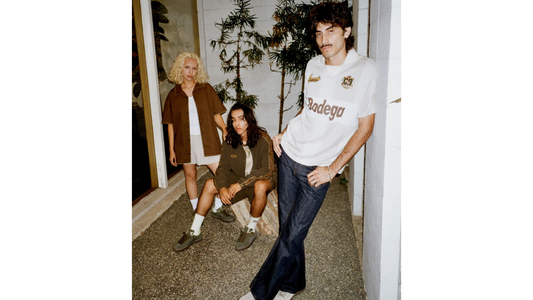

As part of the 2018 NBA All Star Weekend festivities, Bodega and New Era have put their collective heads together once again to celebrate the concept of the Neighborhood All-Star, as photographic and video stories taken over the course of a few weeks highlight playground legends and the local, community-focused side of street basketball culture. The primary subjects of this piece include Dave 'Chino' Villorente, Adam Jason Cohen, and Nick Ansom among others.

The project will culminate with the release of a military inspired capsule collection featuring a range of fitted and adjustable headwear and accompanying apparel pieces, that blends the multifaceted stylistic applications of classic utilitarian wear with NBA team branding.

The NBA All-Star Game is an occasion that brings together the best of the best, top athletes at the peak of the powers, together in one place for an unfettered celebration of basketball. Of course, as any NBA fan could tell you, the All Star game is not exactly a serious, competitive contest, the way that a game seven in the middle of May is. What makes the All Star Game special is the showcase of individual skills. It’s the closest thing pro basketball has to capturing the unrestrained spirit of street level basketball.

A burst of spontaneous, individual creativity being tied back to a more loosely structured, casual form of the game being played is a recurring theme across professional sports. The implication is that the improvised pick up games played as children represent a purer, more joyous expression of playing that is eventually coached out of players.

No sport is more enamored of its street level equivalent than basketball. For every reference to Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi having skills honed on the streets of Portugal or Argentina, when is the last time one of these amateurs became famous in their own right? What is it that makes streetball so unique?

Not to get overly dramatic about it, seeing as how it’s supposed to be an informal activity and all, but it would be entirely fair to say that the practice of pick up basketball games on outdoor courts has, over the years, risen to the level of a full-fledged cultural artform. Whether it’s the positive of proclaiming “and 1” to celebrate a particularly artful maneuver, or the negative acknowledgement of a curmudgeonly, traditionalist coach admonishing his players that “this isn’t streetball,” the form is clearly recognized as its own, distinctive entity.

At its core, the “street” in streetball isn’t a target demographic or an aesthetic; it is an actual, geographical distinction, the old “Anytown, USA” trope, with asphalt in place of amber waves of grain and pie baking contests. But, if there’s one thing that idealized depictions of bygone small towns and actual, modern city life have in common, it’s that the specific location isn’t important; these seemingly random spots on the map are given meaning by the people who inhabit them.

Like any number of things that have been absorbed into mainstream culture from subcultural origins, the idea of streetball has been somewhat reshaped to fit a more convenient, preexisting narrative, namely that the local courts that dot neighborhoods all across the country are, essentially, a humble beginnings stepping stone, something to escape from after you’ve been spotted by the correct people.

It is self evidently a good thing, and cause for celebration when somebody possesses such transcendent talent that they cannot be contained within the chain linked confines of their local court, and actually do move on to bigger and better things, but to focus entirely on the prospect of advancement kind of misses the point of the whole endeavor.

If you’re going to focus entirely on the top of the pyramid, you might as well be inside the Garden, or the Forum. These are palaces of basketball, to be sure, but not everyone is going to be able to step onto the court at a place like that; it’s just a fact of life, a cutting, unfair fact, but a fact all the same. Everyone can, however, participate in some level of streetball. For a majority of streetballers, participation is everything. Not participation in the “everyone gets a trophy” sense that gets so many syndicated newspaper columnists furiously tapping away at their keyboards, but participation in the sense that there is a place for anyone who dares to showcase their abilities, one without any barrier to entry at that.

Simply put, streetball paradoxically transcends basketball by being entirely focused on basketball. By providing a place where status and respect are earned based solely on skill and style, streetball is an avenue for dreaming that where you come from isn’t nearly as important as what you can do.