If you aren’t a dedicated sneaker enthusiast or a serious runner, you could be forgiven for, perhaps, overlooking the New Balance 997. This is not a shoe that made its name with ostentatious colors, technological gimmicks, trendy hype, a nickname bursting with hyperbolic masculinity bordering on the ludicrous, like the “Atomic Shark-Toothed Red Meat Dominator,” or something, and it wasn’t even something that the average, early 1990s kid ran the risk of being ostracized in the schoolyard over. It seems more than a little bit strange to introduce a shoe that is, unquestionably, one of the most coveted models of all time amongst fanatical sneaker collectors this way, but if the 997 could be treated like any other shoe, we wouldn’t be here right now. The 997 is a shoe with a unique story, and at its core, the 997 story is a story about how, even in the most crowded fields, quality can speak for itself, without raising its voice.

The notion that fashion could be an end product of sneaker design, in and of itself, is a comparatively recent phenomenon. Even after various, style conscious youth cultures had made waves in mainstream culture by making fetish objects out of certain models, the basic function, if not the sole purpose of sneakers, was still, ostensibly, the fulfillment of a specific, athletic performance need. Sneaker companies were certainly aware of the weight that aesthetics carried among the sneaker buying public, but considerations like cushioning, stability, support, lighter weight, etc., still reigned supreme. The sneaker retail sector that catered primarily to a fashion audience was a purely niche concern. This athletics-first, performance focused approach to sneakers affected two key areas of sneaker culture, accessibility and design.

As long as athletic performance was the primary purpose of athletic footwear, design evolved along the lines of performance technology. This allowed for a certain level of conservatism to take hold; by and large, sneaker companies weren’t about to fulfill a demand that didn’t exist in the marketplace, just for the sake of novelty. To that end, the basic design and construction of athletic shoes could remain more or less static for decades at a time. For instance, canvas uppers with vulcanized rubber soles were the default basketball court silhouette for so long, that a relatively simple change like the introduction of suede uppers was considered downright revolutionary.

While sneakers are not part of the natural landscape, the evolutionary principle is the same; some level of change in the environment that needs to be adapted to has to occur, to spur change in the organisms. In the world of athletic footwear, that change as the running revolution that would take hold in the United States towards the end of the 1960s. This new fitness movement would change the athletic and footwear landscapes forever, and the responses to it would result in new creations beyond the wildest imaginings of their ancestral forbearers.

At the very beginning of A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens went out of his way to impress upon readers the fact that Jacob Marley was inarguably deceased. This was done in order to ensure that his subsequent, Christmas Eve visit with Ebenezer Scrooge would be received with the gravitas and astonishment consistent with a fateful intervention in the corporeal world by a departed soul. In other words, if you didn’t think he was really dead, it might just look like one guy was visiting his friend’s house. Any discussion of the history of running requires that a similar emphasis be placed on the comparatively recentness of running as a mainstream recreation and exercise endeavor. Chronologically, the sight of humans walking on the moon was “normal” before the sight of humans jogging down a city street or neighborhood sidewalk was. Despite being a basic component of many popular sports, despite boasting an athletic pedigree that dated back to ancient civilization, and despite the relative ease of access offered by an activity that required nothing more than a pair of shoes in the way of specialized equipment, running was considered the sole province of competitive athletes like track and field runners, or boxers training for a fight. The average person just didn’t do it.

The introduction of running as a widespread phenomenon can be principally credited to, appropriately enough, a pair of legendary track and field coaches, Bill Bowerman and Arthur Lydiard. In the 1960s, New Zealand’s track program ascended to internationally preeminent status behind the innovative training methodology of Lydiard. Bill Bowerman and his University of Oregon milers traveled to New Zealand to pit themselves against the sports benchmark, but it was a pleasant, morning outing in an idyllic park rather than any clash of championship runners that would forever change the course of running history.

While Arthur Lydiard’s system of base training and periodization geared towards elite, competitive athletes still influences preparation regimens today, it was Lydiard’s advocacy of recreational running as a means of promoting cardiovascular health and fitness that would end up making an especially powerful impact on Bowerman.

Conventional wisdom in the United States at that time regarded distance running as, at best, unhealthy and, at worst, actively hazardous to the health of its practitioners. Distance running was regarded as especially dangers for women, thanks to the belief that the repetitive impact of foot strikes would damage the reproductive organs. Under these circumstances, Bowerman was somewhat surprised to show up for a morning run organized by Lydiard, and encounter a park teeming with runners, women and children among them. The effort expended on keeping pace with the “slow” group of runners he was placed with quickly outstripped his normal exercise routine, and made a convert of Bowerman. The coach and future footwear innovator would go on to bring jogging back to the sates, and proselytize on its behalf, eventually publishing introductory manifesto, and future best-seller, Jogging, in 1966.

Bowerman’s promotional efforts produced research that would help to dispel the erroneous notion of running as a health risk, and the jogging movement experienced nascent acceptance during the late 60s. It remained enough of a novelty though, for heavyweight, serious media outlets like the New York Times and Chicago Tribune to dedicate column inches, in the tumultuous year 1968 no less, chronicling this strange, new practice and its oddball devotees. Media bemusement was just one, abstract pitfall associated with running; in the early days of the movement, unlucky runners could find themselves grilled or even ticketed by the police. Despite these early hiccups, with the dawn of a new decade, running was about to go from oddball hobby to certifiable boom.

A series of new developments in the early 1970s made the sight of dedicated amateurs logging miles a more common sight. The individual accomplishments of athletes like Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers and Steve Prefontaine were instrumental in bringing a level of name recognition to the sport, the kind of participation boosting reflected glory that inspired people sitting on a couch to lace up a pair of running shoes for the first time. These newly minted runners were able to find more outlets, thanks to the creation of new road races, including events as prestigious as the New York and Chicago marathons. The prospective pool of runners was expanded when by far the most established and most famous American road race, the Boston Marathon, officially began accepting women applicants in 1972. The surge in public interest also led to the creation of a cultural apparatus to support this growing community, as the indispensible Runner’s World went from obscure newsletter to monthly publication.

By the 1980s, running was no longer something that needed to be explained to confused onlookers; it was fully established as a part of mainstream culture.

More importantly, as far as the makers of sports apparel and equipment were concerned, the running boom had become large enough to require technological solutions for an extensive, varied set of specialized problems. Which is to say that the magic word “demand” had been uttered. This is where the story of the 997 truly begins to unfold.

This is editorializing, but one theory as to why running might have, once upon a time, been categorized as a health risk is that old-time runners were setting out in footwear and equipment that wasn’t, at all, properly equipped to deal with the physical strain of even a moderate running regimen. Some people might even say that the running shoes back then, well, kind of sucked. At the time, a lighter weight, leather construction and a modest amount of cushioning represented the pinnacle of what runners could hope to get from a shoe. Much more common was the standard racing flat, which featured stiff leather or canvas uppers and flat soles with negligible cushioning properties. Although improved versions of the flat, with improved flexibility and fit were popular with some marathon level runners, new technological developments made it abundantly clear what qualities were in demand, and where the future of running shoe design was headed: cushioning.

The first running shoes to feature cushioning were revolutionary simply by existing. A new material would take things to the next level. Ethyl-Vinyl Acetate, more popularly known in the sneaker world as EVA foam, is a versatile copolymer with a wide variety of industrial applications. One form of EVA boasted soft, flexible qualities comparable to rubber, making for bouncy, cushioned midsoles that not only became the industry standard of the era, but is still the mostly commonly used running midsole today. While runners rejoiced over this technical bonanza, the impact wasn’t just felt beneath their grateful feet. Accommodating and optimizing these new features ushered in a sea change in the physical appearance of shoes. Lighter weight textiles like nylon, and later mesh, replaced leather as the standard upper, allowing new shapes like the wedge and space shuttle to replace the simplistic flats of old.

The physical design of shoes would continue to evolve in response to new, performance needs. The importance of stability and motion control became the next big issue for running shoes to address, so another new decade became another new technological leap forward.

One brand who went above and beyond in seizing the brass ring during this era of performance driven innovation was New Balance. The brand had been a favorite among runners since the earliest days of the movement, and during the 80s their purist approach to progress would cement their status as a true, runner’s running brand. The 99x series, introduced in 1982 with the debut of the New Balance 990 put a very simple idea into practice, make a running shoe that offered the best available version of every possible feature: pigskin suede, dual density cushioned midsoles, motion control equipped heels, even the first ever reflective 3M accenting, all made right in the USA. This combination of cutting edge tech and superior construction made the 990 the first running shoe to break the $100 price tag, an eye-watering figure by the standards of the era, but as it turned out, the price tag proved to be no obstacle.

The 990’s high price tag would prove to have an ancillary effect. While far from mainstream, the prospect of a purely fashion driven sneaker culture had reared its head by the dawn of the 80s. With factors like image based marketing and cultural perception established as crucial factors in the overall package presented by a shoe company, New Balance’s combination of performance driven technical excellence, top of the line quality and no-nonsense yet sophisticated aesthetic sensibility became a signifier of refined taste, authenticity and exclusivity, a mark of true connoisseurs. New Balance was not shy about their newfound position either. The brand’s status as a bastion of authenticity and quality in an increasingly trendy, superficial, hype driven world was leveraged with an aggressive ad campaign that directly criticized competitors.

This sterling reputation would prove invaluable as, in 1990, New Balance unleashed the first extensive update of the original 990, the legendary 997. Spearheaded by designer and his development team, a mandate to modernize saw significant design changes, both external and internal instituted with the goal of the offering the most advanced performance shoe that New Balance was capable of making. The industry standard EVA cushioning was replaced by an innovative, multifaceted series of upgrades. Dual density ENCAP inserts that surrounded an EVA core with a polyurethane shell and C-CAP cushioning, a compression molded form of EVA with a greater level of flexibility, from the toe to midfoot. Tri-density outsoles, featuring an XAR-1000 carbon rubber heel and a Hytrel thermoplastic collar lockdown strap that connected the shoe’s top eyelets to the heel counter, provided a critical, visible technology element. Even the signature, tonal grey palette of the 99x series was taken to new heights, as the traditional suede/mesh build was complimented by dimpled “basketball” leather, adding to the ultra refined aura.

A hit with runners (including a prominent resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, if certain urban legends are to be believed) and style fiends alike, the 997 ascended to something akin to holy grail status thanks to its comparatively short time in the sun, and subsequent disappearance. Performance running shoes are, by nature, designed for obsolescence, so the 997 being removed from the active rotation of performance silhouettes in 1994 would have been pretty standard, but the events that followed are the stuff of conjecture and debate to this day. Unlike countless other popular performance models that made the transition into the lifestyle sphere, the New Balance 997 was not reissued; in fact, it dropped off the face of the Earth entirely. The most common, but by no means officially confirmed, theory is that the original molds and lasts were lost during a factory move, and too expensive to bother replacing. Adding to the tragedy factor in this tale of footwear woe is that one of the 997’s defining features, the polyurethane shell that encased the performance technology, actually accelerated the shoe’s extinction. As any sneakerhead is well aware, polyurethane decomposes over time, reducing even the most lovingly tended pairs to crumbling ruins. By the end of the decade, it was an exceedingly rare sight to see a pair of 997s on foot, in the wild.

Even as sneaker culture took off, establishing itself as an integral aspect of mainstream popular culture, spreading the legend of the 997 to a wider audience in the process, it remained a purely archival item. Appropriately though, for a model whose flame was kept alive by a cadre of hardcore fanatics, the first signs of a 997 revival were limited edition collaborations with Japan’s United Arrows & Sons, in 2008, and Nonnative, in 2011. The catch was that the original 997 remained lost to history. These collaborative releases featured a new silhouette, dubbed the 997.5, which featured the 997’s upper affixed to the 998’s ABZORB equipped sole unit. The not quite the historical original construction, combined with the relative difficulty of obtaining a United Arrows or Nonnative 997.5 served to tantalize fans even further, eventually bringing popular demand to a breaking point. In 2014, a full twenty years after the 997 had first disappeared from public view, New Balance acceded. The original, made in the USA, tonal grey 997 made its full-fledged return.

What’s truly remarkable about the 997’s time in sneaker purgatory, is that even though the primary audience of the shoe completely shifted, from performance running to fashion, the essential point of the 997 never changed. The insane levels of hype were purely incidental; people would have been just as happy to have the 997 consistently available during that twenty year gap. Just as runners looking for a top of the line shoe in the early 90s eschewed the hype driven marketing and cosmetic bells and whistles typical of the era, the future tastemakers who spent years coveting, hunting down and generally obsessing over the sleek design, technical excellence and luxurious materials, did so out of a genuine appreciation for one of the best running shoes ever made.

Now that the 997 is back, New Balance aren’t content to let it rest on its laurels. Athletic performance technology isn’t a field where nostalgia holds a lot of clout, and the spirit of the 997 has always been its every day wearability. No one remotely serious about their running ever skipped a day because their shoes didn’t quite match their outfit, or because they might be exposed to the rain and compromise their box fresh condition.

With the reborn 997 set to tackle new frontiers, this legendary silhouette has undergone an evolution, from every day running to every day life.

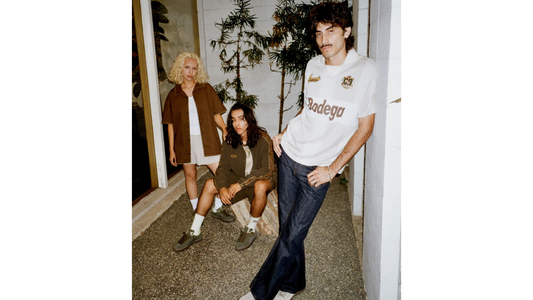

The debuting New Balance 997H silhouette is an instant classic for a new era. Inspired by Steven Smith’s original design, this streamlined take on the 997 brings 90s style to modern comfort. The shift from standard EVA to ENCAP and C-CAP technology is mirrored in the 997H’s use of Ground Contact EVA, a foam that is injected into the shoe, rather than layered, for improved durability and responsiveness. A high grade, synthetic leather, suede, and mesh upper is rendered in 90s appropriate colorways and paired with an updated, lightweight outsole.

Of course, all of these upgrades don’t really mean anything if the 997 doesn’t pull its weight in the field. To that end, we outfitted the embodiment of every day reliability, the local mail carrier, with the 997H. When your job comes with a creed that lists the things that won’t stop you from doing it, your shoes better be up to the challenge. If rain, sleet and snow aren’t supposed to stop the mail, then uncomfortable shoes really aren’t going to cut it as an excuse.

Despite the twists and turns that a journey of three decades is bound to include, one thing has never changed. There is no singular 997 image. Wearing it won’t make you a pioneer, and it won’t make you a system-bucking rebel. Wearing it won’t even, necessarily make you a runner. The only thing that happens when you are wearing the 997, is that you are wearing the 997. If you want it to mean anything more than that, you have to put them on, take them outside, and go do something worth remembering yourself.