From his star-crossed introduction to art at an early age through his career in graffiti, graphic design and beyond, Eric Haze is your favorite street artist’s favorite artist in a way that is uniquely not esoteric, obscure, or pretentious, but approachable.

Playing a vital role in the early days of graffiti along with some of the biggest names in art, full stop, “Haze” as he is known was instrumental in bringing the movement above ground and growing the legitimacy of the art form.

Balancing his purist integrity with the desire to have his work seen by the world, Haze was a pioneer of marketing his tag and was way ahead of the curve when it came to building a brand around it – a brand that continues to evolve and innovate today through an ever growing list of collaborations, projects, and experimentation across mediums.

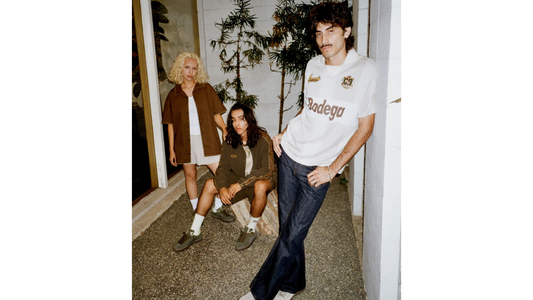

To mark an upcoming capsule we have in the works for Delivery #02 of our Bodega Autumn/ Winter ’22 campaign, we put Haze in the hot seat to learn more about the man behind the tag including his experience in the early days of graffiti in New York, origins of his graffiti name, his thoughts on the current state of street fashion, advice for next-gen artists and so much more.

Thank you for time Eric, we really appreciate it!

Q: Is it true you met Elaine de Kooning when you were little? What was that like and was she the first professional artist you ever met?

A: To sort of put it in a simple time code, I was exposed to a lot of modern art when I was a kid by my father – pop art, abstract art, and through a friendship he had at Columbia University where he taught, ultimately as a sort of mutual favor with a friend, I had my portrait painted by Elaine de Kooning when I was 10 years old. She actually mentored me in abstract oil painting at the time. I’ve got 2 pretty remarkable abstract canvases that I stretched myself under her tutelage.

But the real story is that a year later at 11 years old, graffiti came along and kind of wiped the slate clean in terms of the aesthetics and who I sort of ended up imagining myself to be as an artist.

Q: Did it take this exposure to the abstract side of things in order to pivot into graffiti or was that just separate?

A: You know, writing graffiti was almost automatic. I lived on the Upper West side off Broadway at sort of the epicenter of the first generation of graffiti and you know it was sort of like vegetation growing all around us that just caught our attention. Everybody on the block wrote graffiti. By 11 years old I was off to the races in the pursuit of some identity and the thing about graffiti is, even in its lowest forms it’s always been aspirational. There is an understanding that you start from zero and you aspire to develop style in order to gain acceptance and gain recognition. So graffiti was sort of a great creative motivator in the way that – we couldn’t intellectualize it at 11, 12, 13 years old but it bore fruit for those of us that stuck with it.

We chose these two letter names for speed and efficiency of bombing and doing throw ups but then everybody typically had what was called a backup name which would be a longer name that you could sort of flex more style using more letter forms.

Q: It definitely seems like an art form where you have to keep at it as opposed to tagging one thing and getting worldwide recognition – it's a slow build.

A:I’ve always looked at it like a sport. It was a sport we played in our youth that in a way, before its popularity and recognition, was sort of an insiders code. We were only speaking to each other, not to the world. It was a good proving ground for a lot of things.

Q: In those early days what was the routine like on a day you were going out to tag/write?

A: There was always an element of exploration. In my era, graffiti was permanently tied to the landscape of the city so as a kid from Manhattan we heard the folklore of the Bronx and the folklore of Brooklyn. I was the kid that would cut school and just ride the trains, exploring different yards and neighborhoods. 13 years old, long hair, walking around the wildest parts of east New York and the south Bronx in the early 70s.

Q: Concerning the geography then and all these different landscapes, what was the transition like going from underground graffiti to above ground?

A: If you look at my history and my career I’m probably one of the few from my generation who didn’t set out to prove that graffiti was supposed to be recognized as an art form or accepted. I was more of a purist. Even when I understood there was a career ahead of us, I tried not to confuse the sport and the passion; a career and wanting to create value with wanting to sort of put my fingerprints on the world above ground. I saw that as a different challenge and a different set of criteria. Sort of starting from scratch again the way we had started from scratch as kids, coming up with a name and sort of building a style and identity around it. And when it was time to make tougher real world decisions about a career and making a living I understood that it was back to a different square one, to establish style and identity above ground.

Q: Talking about identity, do you remember the origins of your tag? Do you remember the first time you wrote it?

A: I do, my original graffiti name was SE3. There was a group of friends from my neighborhood. One friend wrote JE, another friend wrote ME and my other friend wrote SIE. So we all sort of clicked in terms of how we approached our names. We chose these two letter names for speed and efficiency of bombing and doing throw ups but then everybody typically had what was called a backup name which would be a longer name that you could sort of flex more style using more letter forms. "Haze" was originally my backup name and I do remember the night I came up with it, tripping my brains out listening to Jimmy Hendrix “Are You Experienced”.

the fact that everybody is looking through the same lens, at the same material with the same menu sort of makes originality harder to come by...

Q: Talking about your upbringing, friends, neighborhood, etc. how important was it that you grew up in New York City to stoke the graffiti flame?

A: 100%. I am a 3rd generation Ellis Island New Yorker and it’s fair to say I would be a completely different animal had I not grown up in New York. Nature or nurture, I say both.

Q: What about growing up in the time you did versus today with the impact of technology. Would you still have gravitated towards graffiti or maybe digital art or even something entirely different?

A: Impossible to say, but you know, I’ve been pretty analog my whole life despite the growth of the digital world and technology. It’s a bigger conversation but you know there are plusses and minuses in terms of what we’ve gained and lost with technology and modern media.

Back 30 years ago, if you wanted to know what was going on in New York, you had to come to New York. The same was true in fashion with trade shows. If you wanted to know what was going on in streetwear in 1995, you had to get on a plane and go to a trade show and see what everybody was doing. So in a way that required greater motivation and greater participation and sort of a boots on the ground approach in the culture. Whereas now there is a tradeoff. You don’t need to work that hard to find out what’s going on so that’s probably good. The access to information and style is a good thing. But the fact that everybody is looking through the same lens, at the same material with the same menu sort of makes originality harder to come by, in a world where everything is exposed and in some degree disposable.

Q: So do you think that boots on the ground approach that you kind of needed to navigate 'what was what' influenced you turning your tag into a branded logo – I read you were the first to do so basically?

A: To put that into perspective its probably fair to say I was the first and the only one of my generation who sort of took a hard left turn into design, branding, and the world of commercial art. In the 80s when I made these decisions, graphic design and product were sort of antithetical to the idea of being an artist with a capital “A”. It still was an era where people would cry sellout over that kind of thing where to me, one of the fundamental reasons I chose the path of graphic design and embraced commercialism was that I wanted to put my fingerprints on the world.

I wanted to participate in things that were sort of greater than the individual – be that movements like streetwear, graffiti coming above ground, the power came from community as much as individuality. I felt like coming from graffiti, I came from a very populous medium. And a very populous radical set of politics. Back then embracing what I perceived to be the elitism of the art world and the preciousness of individual objects, I came up with sort of an equation in my head that if there was a choice between creating one disposable piece of work that was worth a million dollars to one wealthy customer versus creating a million stickers for $1 each and getting them out to an audience of a million people, the choice was clear that mass production and commercialism was more consist with the populism of graffiti and my roots.

So those choices were based on a philosophy not just an economic model. Fast forward now 30-40 years later and the beauty is the walls have come down. These preconceptions of what’s art versus what’s product versus what’s design versus what’s fashion – those 4 worlds lived very separately on their own terms once upon a time. And now in a legacy that goes back to Andy Warhol sort of flipping the idea of product and perception in his art, then Keith Haring challenging that in terms of playing both the high and low art games at the same time, after which a rarified handful of us followed suit by straddled fine art, branding, product and pop culture at the same time. Now, a lot of these things that seemed like separate lanes once upon a time have all blurred into one sort of creative playing field. These days, art can be very populous and product can be very rarified.

if there was a choice between creating one disposable piece of work that was worth a million dollars to one wealthy customer versus creating a million stickers for $1 each and getting them out to an audience of a million people, the choice was clear

Q: That’s the energy and context you’re brining to fine art as well, you can tell you’re pulling everything that you’ve learned while evolving, to this new world/space.

A: Well thank you, I sort of threw my hands up in the air and walked away from the gallery world for probably 10-15 years. And part of that was I felt like when Keith and Jean passed away and there were sort of hard times at the end of the 80s for everybody I think that that conversation seized to be vital for a while. Like it was a very vibrant conversation in the 80s and that conversation had sort of ended to a degree and new conversations were sparked.

Now over this period of time I’ve challenged myself in different ways but I did have another unexpected awakening when I had the opportunity to do a residency at Elaine de Kooning’s studio two and a half years ago. This connected me to something from that formative time, before graffiti that I never really had time to unpack. So when I did this residency, I took it as a golden opportunity to explore and unpack who I might have been if graffiti hadn’t come along and how those very formative influences would have shaped who I am as a graffiti artist and a graphic designer. So in the course of that, it was one full blown transformative revelation as a painter, as an artist, as an abstract graphics guy.

Q: Can you elaborate on this transformation?

A: I rediscovered reality, I rediscovered figurative work, portraiture, and it became my embrace and transition of starting to find new and unique meaning in other people’s lives, other people's work and the world around me. The same way that I had chosen graphic design because I wanted to put my fingerprints onto the world, after all these years of 'doing me' and ‘what does Haze stand for?’ and ‘how does Haze express himself?’, one day Eric woke up and he was equally interested in everybody else’s story and how it all connects. Recently, I’ve done portraiture of my contemporaries and different scenarios through the history of my life both autobiographical and external. It's all part and parcel of my increased and new found interest in our commonality and what connects us through experience and perception.

Q: A truly full circle experience it sounds like.

A: What took a while to shake out was I thought I needed to distance myself from people’s perception of me as a graphic artist in order to be understood as a painter. But I came to realize that was just a false construct in my own head. That everything I did even though it may be different mediums and different terms, I knew everything was connected and I sort of had a confidence that my audience would also understand how to connect these things that were at the core. Plus the fact that I still have all the opportunities and avenues as a designer, as a brand, and as an art director, it remains increasingly clear that still having these opportunities allow me a different comfort zone and ability to take risks as an artist that I might not otherwise have been able to take if I was really just trying to pay the bills as a painter.

Working with Bodega is also as much an example of connectivity and commonality as the paintings I described. It's not just ‘the sum of the parts is greater than the whole’, we all put our money where our mouth is when it comes to community, and these collaborations say to the world that we appreciate each other and we respect each other and that there is something unique we can offer the world when we hold hands.

Graffiti always had accepted healthy competition built in. Outdoing the next man. And that’s traditionally what schools of art are. Schools of thought. Groups of people that are sort of pushing each other’s envelope.

Q: Switching gears a bit, what was it like running with Futura, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and all those guys?

A: There was a great sense of excitement in the air during those days. It was a little like "the blind leading the blind" because everything was new and we were making it up as we went along, everybody was. There was a profound sense of community. Everybody had their own quirks. We were a bunch of rough around the edges, fundamentally anti-social kids. Some people like Keith brought an out-of-towner’s spirit of generosity. In some sense I always understood the difference between those of us who were born into it in NY, like Jean-Michel, Futura was born into it but then you looked at the Keiths and the Andy Warhols or even the William Burroughs’, these are people from middle America who for whatever reason understood there was a different reality waiting for them in NYC. In a way some of us had these childhood identities that we were handcuffed to and had to figure out where as people like Keith got to come to NYC and shed an old skin and re-invent themselves. There was a very symbiotic relationship between those two things. I always feel like the out-of-town-ers could see things in a way that we couldn’t because we’re too close, but we have this DNA that they’re aspiring to. It was really an exciting time.

But you also have to remember, there’s a subtext to this that has to do with economics and the cost of living. One of the things that makes our era a rarefied time creatively was that the cost of living so cheap, New York City was so beaten down that we could share 2 bedroom apartments that cost us $400 a month. So when your rent is $200 a month - I drove a cab two nights a week, I sold some weed, you know, it was much easier and possible to slum it for a few years while you figured out which way was up. Now the city and the economics of the city and life in general is so brutal here. You can’t come to New York and tread water finding yourself for $4000 a month the way you could at $400. That’s another modern era mixed blessing. That comfort zone is gone but it really drives people to excel because it's make it or break it.

Q: Interesting that you say "blind leading the blind", you guys were on the forefront, the first generation of the graffiti movement, you didn't have a previous generation to look to, so was it more that you were pulling inspiration from other worlds which lead to so much originality and firsts?

A: Fair enough. Back to what I was saying about graffiti being aspirational, graffiti also always had accepted healthy competition built in. Outdoing the next man. And that’s traditionally what schools of art are. Schools of thought. Groups of people that are sort of pushing each other’s envelope. One of the subtexts of that era is that there was a lot of greatness floating around. And everybody wanted to figure out, was there a way to bottle greatness for yourself. I think as we saw people like Keith and Jean rise, it had a sobering effect that the possibility was there. You could go from writing on chalk and on subways to taking over the world and achieving great wealth. It also proved that those were no accidents and that having a glint in your eye was one thing but realizing it in the eyes of the rest of the world was a greater, less predictable challenge. To a degree we were the generation with zero road maps, zero references, zero people available to guide us in a totally unknown new world.

The generation that followed us, the Shepards, the KAWS’, the legit next gen were the people in the stands, watching. For all the possibility the world held for us, it also held the possibility of making terrific mistakes and fucking things up along the way because we were not sophisticated, because we were just winging it, and because we never really had a plan. So god bless the next generation that was able to watch us and go ‘he made that choice and it didn’t work, that’s a choice to stay away from’. ‘He put on that uniform and scored a goal so that’s a viable option’.

Everybody from this generation all the way up to Virgil have been the beneficiary of those lessons learned and the hard knock school we came from. Frankly, it meant and means a lot when people like him would reach out behind closed doors and say ‘Hey just want to let you know, respect and appreciate the fact that we wouldn’t be here if you all didn’t provide a foundation'. The truth is, streetwear and what is now considered street luxury all come from the seeds our generation planted.

Q: You mentioned it above but people may not know about your involvement in the music industry, can you talk about that time in your career?

A: When I talk about graffiti above ground and that movement, it went boom and bust to a degree by the end of the 90s. The way I look at it are hot mediums. So if being a painter or opening a gallery was the hot medium in 82, 83, by 89, 90, 91, music and hip hop specifically became the hot medium.

It’s sort of the chicken and the egg for me, I made the decision to go to a school of visual arts, worked on my portfolio, studied typography, and learned my chops before the invention of the Mac. I went to school to learn production values that were up to par with my creative skills in order to cut it in the real world. I had the vision that I could forge a new career in graphic design. Ultimately, music as the hot medium at the moment allowed me to apply my skills and style while continuing to put my fingerprints on the world through this product.

When I set off to be a graphic designer, logos and album covers were top of the list. There was a direct thread. I came from a world of lettering design and no matter what angle I looked at it from, the written word was at the core of what I did. It is what I was passionate about. In a purely commercial sense I understood that I had spent my life developing my identity and I could probably make a mark and a living helping other people develop their identities in visual and graphic terms too. I was fortunate to enter that atmosphere in the tail end of that era. While there were still 12” record covers. The art was still something tangible you could hold in your hand and resonated differently than it does now on screen in the digital age.

Q: So when you mention finding solutions for different artists does, for instance the Beastie Boys or Public Enemy, does that come from listening to the work and going from there or directions from their team, etc.?

A: It can be either or, there is no one methodology. I tend not to focus on the music itself. How it sounds is someone else’s responsibility. I sort of look at it like what’s the identity of the subject. How can I capture in visual terms who they are and what their music represents to people? Two very different aesthetics with two very different results would be LL Cool J’s “Bigger and Deffer” – which was really hard edged, like LL said something about doing graffiti and I was like 'No this isn’t a breakbeat album', and we have to come harder than that. And when LL saw [the finished product], he gave what I consider the greatest hip hop compliment, which was ‘Yo that looks like getting paid’.

So that was the aesthetic for that lane of hip hop. But if you look at the Beastie Boys years later, which is also hip hop, completely the opposite. I took my queue from MCA saying that he wanted [Check Your Head] to sound like it was recorded on a toaster oven. I went low and brought a low fi type of vibe, which wasn't about looking like you were ‘getting paid’ but JUST like you were doing cool shit.

Q: I have to ask, New York reality check 101, can you talk about this mixtape? There isn’t a lot out there about it and considering how influential it went on to be, I’m sure a lot of people are curious.

A: That was a beautiful one-off project Preemo and I did on Payday label but the seed of that is that - underground being the operative phrase - Pay Day was actually an underground night club in NYC before it was a record label and I was the art director for the night club, doing all the flyers, street snipes, and posters. One of the founders, Patrick Moxey went on to start a record label of the same name. So when they decided to do an underground compilation, we got the band back together for that, from the night club days. I think that might have been the only compilation that Pay Day put out but that was a terrific honor and opportunity to do that with Preemo. We shot that album cover gorilla style in the abandoned subway station on 91st and Broadway. I grew up there, it was my training ground before the trains, before the train yards. It was a one off special record from a special time but it was born out of the underground club scene.

Q: Between running your own brand and the ever-growing list of collaborations, what has the role of clothing and personal style been throughout your career?

A: In some ways I’ve always considered myself the medium more than the message. I don’t wear a lot of graphics usually because I sort of exist in that world and I’m always channeling one thing or another. It’s just sort of who I am, sort of dressing somewhat neutral. I’ve been in a black t-shirt and white kicks since the Orchard street days in the early 80s. What I will say is over the last 5 years my interest and attention span in fashion particularly has been very much reinvigorated and it’s a combination of increased level of participation again and new era relationships – with Virgil, Poggy in Japan, Sandra Choi in London – I’ve been surrounded by people with really eclectic terrific fashion sense. I owed it to myself to up my on court IQ about fashion again. And it doesn’t mean that I've become more fashionable or dress a whole lot different although - I’ve had my red carpet moments in the last few years… I’m really happy that this generation of elevated street fashion has truly inspired me to pay attention and give a shit again.

Q: That’s a great message, there is this vibe that people are too cool to be excited about what’s going on and aren’t seeing the positives but new ideas and refreshing takes make it a time to be optimistic.

A: The bottom line is to remain excited about what you’re doing every day and have some latent belief that the next thing that comes your way might be the most exiting thing ever. And that requires participation, enthusiasm, and commitment and those all become self-fulfilling prophecies in positive or negative terms depending on how you apply them.

We’re all unique individuals and to some degree creativity is proportional to putting something unique out into the world...

Q: What’s inspiring you right now in terms of art?

A: The wide world of possibilities. I pinch myself most days that I’m still here and I value the creative freedom and unlimited opportunities that are both something that I’ve earned and something I’ve been blessed by.

Q: For the up-and-coming artists out there looking to get their art seen by the world, do you have any advice?

A: My advice might sound somewhat cliché but “Do you”. We’re all unique individuals and to some degree creativity is proportional to putting something unique out into the world that can only come from your heart or your hand or your head. In a world where there are no guarantee and tomorrow isn’t even guaranteed, you have to be willing to fail to succeed and you learn more from your mistakes than your successes, so try to keep a balance to it.